Beginning this module was daunting. I have little experience with linear algebra and had never performed a Principal Component Analysis before. I have since completed this part of the module and feel a little more comfortable with using the terms and the associated concepts. This post will serve as documentation of my progress and a method to solidify the notes I have taken.

The directions on this part of module 1 are as follows:

Gemini 2.5 Pro

Linear Algebra in Action:▪ Implement Principal Component Analysis (PCA) from scratch using NumPy. You will not use a pre-built library for this part. This will involve calculating the covariance matrix, finding eigenvectors and eigenvalues, and using them to transform the data.▪ Project Goal: To understand how we can "squash" high-dimensional data into a lower-dimensional space while preserving the most important information.

The first step was obtaining a wine dataset. After a cursory search and setup of a Kaggle account I selected this dataset. This wine dataset has 11 input features, 1 output feature, an ID column, and a total of 1143 entries. This provided plenty of dimensionality to work with for a dimensionality reduction exercise. And the size of the dataset was quite manageable at 77 KB.

As I went through this exercise I dove into the implementation before looking up the definition of Principal Component Analysis. I got a practical definition from Gemini but this did not quite sink in at the time. I did eventually become curious and look up the definition which I will reproduce here for the sake of flow.

Principal Component Analysis: A statistical method to reduce the dimensionality of data while preserving most of the data’s variation. This is a linear method that finds principal components that cluster along a straight line. Non-linear PCA and other methods may be used when data has non-linear clusters.

My first step was to load the dataset into my Python script. I used the Python library Pandas to accomplish this.

import pandas as pd

wine_dataset_file = "WineQT.csv"

wdf = pd.read_csv(wine_dataset_file)

As I went through this process I continued a back and forth with the Gemini 2.5 Pro notebook that I used to generate the initial course structure. It had suggestions, beginning with using Pandas, for how I should proceed. As I had never performed PCA before I found these quite valuable. Among them was checking the dataset for any missing values. While the dataset was rated as high quality on Kaggle I wanted to practice methods. I used the following Pandas methods to do basic data sanity checks, check for null values and not-a-number values. I also put the input columns into a list (wdf_columns_input) for use later in the script.

# verify dataframe loaded properly

print("==DATAFRAME SANITY CHECK==")

print(wdf.head())

print("\n==DATAFRAME INFO==")

print(wdf.info())

# check for missing values

print("\n==NULL COUNTS==")

print(wdf.isnull().sum())

print("\n==NaN COUNTS==")

print(wdf.isna().sum())

wdf_columns = wdf.columns.tolist()

#print(wdf_columns)

exclude_columns = ['quality', 'Id']

wdf_columns_input = []

for column_name in wdf_columns:

if column_name not in exclude_columns:

wdf_columns_input.append(column_name)

Gemini provided me with a practical definition of PCA at this point and the concrete steps for implementation. These are reproduced in abridged form below.

The first part of our project, “The Geometric Interpreter,” involves using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to visualize your 11-dimensional wine dataset in a more human-friendly 2D or 3D space. Imagine trying to understand the relationship between all 11 physicochemical properties at once. It’s impossible for our minds to picture. PCA is a mathematical tool that helps us find the most informative 2D or 3D “shadow” of that complex 11D object.

Gemini 2.5 Pro

1. Standardize the Data: Ensure all variables are on the same scale (e.g., mean of 0, standard deviation of 1). This is crucial because a variable with a large range (like total sulfur dioxide) would otherwise dominate the covariance calculation.

2. Calculate the Covariance Matrix: Compute the 11×11 covariance matrix from your standardized data.

Find Eigenvectors and Eigenvalues: Decompose the covariance matrix to find its corresponding eigenvectors and eigenvalues.

3. Rank the Components: Sort the eigenvectors in descending order based on their eigenvalues. The eigenvector with the highest eigenvalue is your first principal component (PC1), the second is PC2, and so on.

4. Transform the Data: To create your 2D plot, you will take your original 1597×11 data matrix and multiply it by a matrix made up of your top two eigenvectors (PC1 and PC2). The result will be a new 1597×2 matrix. These are the coordinates for each wine on your new “Geometric Map.”

The first step involved calculating the standard deviation and mean of each feature column and using them to compute the z-score, or Standard Score. Computing the z-score for each data point accomplishes normalizing the units between feature columns. This is important so that PCA does not produce misleading results with overstated importance on features that are drastically off-scale from each other. The wine dataset has the following feature columns, mostly with different scales and units: fixed acidity, volatile acidity, citric acid, residual sugar, chlorides, free sulfur dioxide, total sulfur dioxide, density, pH, sulphates, alcohol.

With an idea of what standard deviation was I proceeded to write Python code to accomplish this in two functions. For reference, standard deviation is a technique to quantify the amount of variance in a set of data. In the wine dataset a feature column with a high standard deviation, total sulfur dioxide (32.78), indicates that the numbers in this feature column are spread far and wide along the number line and do not cluster as much as other features around the mean (45.91). In contrast the alcohol feature has a standard deviation of 1.08 and mean of 10.44 indicating the numbers in this column are not as spread out along the number line as the values in the total sulfur dioxide column. There are functions included in the Python Numpy library that would have done these calculations for me but to gain a deeper understanding of what was going on I decided before I started this module that I would implement as much of these part as possible.

def calculate_mean(series):

summation = 0

for value in series:

summation += value

mean = summation / float(len(series))

return mean

# calculates population standard deviation

# returns population standard deviation and mean

def calculate_standard_deviation_and_mean(series):

"""

Subtract the mean from each individual element in the list.

Square each of these differences.

Sum all the squared differences.

Divide the sum of squared differences by n.

Take the square root of the variance.

"""

mean = calculate_mean(series)

squared_sum = 0

for value in series:

difference = value - mean

squared_difference = difference ** 2

squared_sum += squared_difference

population_variance = squared_sum / float(len(series))

population_standard_deviation = math.sqrt(population_variance)

sample_variance = squared_sum / float(len(series) - 1)

sample_standard_deviation = math.sqrt(sample_variance)

return population_standard_deviation, sample_standard_deviation, mean

A note on population vs. sample standard deviation. I initially wrote the standard deviation function to calculate only population standard deviation. I later added sample standard deviation when I realized the dataset had 1597 IDs but only 1143 wines. This correction is called Bessel’s correction. I understand the use case and that it makes the calculated standard deviation slightly larger. I am still wrapping my head around what it means, exactly. To be specific, Bessel’s correction is used when working with a sample dataset that does not include the entire population. According to what I have looked up when calculating standard deviation from a sample of a population there is a tendency to underestimate population variance because the sample mean reflects the sample data points and not the data points of the entire population.

After writing the functions to compute standard deviation and mean I proceeded to calculate these for each input feature column in the wine dataset. I used the built-in Pandas std() method to check my work. I stored my computed values in the pstd_mean_wdf_inputs dictionary for later use. With column name as the key and a list [population_standard_deviation, sample_standard_deviation, mean] as the value.

pstd_mean_wdf_inputs = {}

for column_name in wdf_columns:

if column_name not in exclude_columns:

pstd_mean_wdf_inputs[column_name] = []

# calculate the population standard deviation and mean for each column

# store in pstd_mean_wdf_inputs as [population_standard_deviation, mean]

for column_name in wdf_columns:

if column_name not in exclude_columns:

population_standard_deviation, sample_standard_deviation, mean = calculate_standard_deviation_and_mean(wdf[column_name])

print(f"\n{column_name}:\n sample standard deviation={sample_standard_deviation} mean={mean}")

# setting delta degrees of freedom to 0 makes the calculation variance / n - ddof

print(f" pandas sstd={wdf[column_name].std(ddof=1)}")

pstd_mean_wdf_inputs[column_name] = [population_standard_deviation, sample_standard_deviation, mean]

I then had the task of computing the z-score and creating a new standardized Pandas dataframe. Computing the z-score of all values in the dataset is important because it recalculates the data in a feature column to have a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. This gives a standardized scale across all feature columns regardless of the scale and units of the original feature column. I think this is kind of neat.

I accomplished this by creating a Python dictionary with all the input column names as keys and empty lists for each value. I then used the Pandas iterrows() method to iterate through all the rows in the dataframe and compute the z-score for each value. When I wrote this part of the script I had not yet added the wdf_column_inputs list and used the excluded_columns list to skip adding the quality and ID columns to the zscore_wdf_inputs_dict. At the same time I constructed a zscore_wdf_dict that included quality and ID columns in case I needed them later. I then converted the dictionaries into Pandas dataframes and the zscore_wdf_inputs dataframe into a Numpy matrix for further calculation later. The code I used to accomplish all of this follows.

zscore_wdf_dict = {}

zscore_wdf_inputs_dict = {}

# prepare the new dataframe for the z-score

# include quality and Id columns so that

# rows can be linked back to their original rows directly

for column_name in wdf_columns:

if column_name not in exclude_columns:

zscore_wdf_dict[column_name] = []

zscore_wdf_inputs_dict[column_name] = []

else:

zscore_wdf_dict[column_name] = []

for index, row in wdf.iterrows():

for column_name in wdf_columns:

if column_name not in exclude_columns:

population_standard_deviation = pstd_mean_wdf_inputs[column_name][0]

sample_standard_deviation = pstd_mean_wdf_inputs[column_name][1]

mean = pstd_mean_wdf_inputs[column_name][2]

z_score = (row[column_name] - mean) / sample_standard_deviation

zscore_wdf_dict[column_name].append(z_score)

zscore_wdf_inputs_dict[column_name].append(z_score)

else:

zscore_wdf_dict[column_name].append(int(row[column_name]))

zscore_wdf = pd.DataFrame(zscore_wdf_dict)

zscore_wdf_inputs = pd.DataFrame(zscore_wdf_inputs_dict)

zscore_wdf_inputs_matrix = zscore_wdf_inputs.to_numpy()

print("\n==Z-SCORE WINE DATA==")

print(zscore_wdf.head())

With the z-scored wine data in hand I proceed into calculation of the covariance matrix. Specifically the sample covariance matrix because I used Bessel’s correction during the calculation. To calculate a covariance matrix one must take two feature columns and multiply each row’s values together. These multiplied values are then added together and divided by the number of rows minus 1. This process repeats until every column has been combined with every other column. This results in a new matrix that is n x n where n is the number of columns in the dataset.

I will make this more concrete with some examples from the wine dataset. Again, the input columns in this dataset are fixed acidity, volatile acidity, citric acid, residual sugar, chlorides, free sulfur dioxide, total sulfur dioxide, density, pH, sulphates, alcohol. The first row in the wine dataset sample covariance matrix contains the sample covariance of the fixed acidity feature with every other feature, including itself. The first cell in this row is the sample covariance of fixed acidity with fixed acidity. The second cell in this row is the sample covariance of fixed acidity with volatile acidity. The next is the sample covariance of fixed acidity with citric acid, and so on. This repeats for every column in the dataset, resulting in an 11 x 11 matrix. This matrix is mirrored across the diagonal. Meaning the matrix has the same values for row 1 column 0 as row 0 column 1.

For a sanity check on the data I first calculated the diagonal of the matrix which is each column multiplied with itself. I was initially concerned because all the values for the diagonal were the same. After some research I learned this is a feature of z-scored data.

# calculate covariance matrix diagonal for sanity check

# for z-scored data this should be approximately 1

print("\n==Z-SCORE VARIANCE==")

for column_name in wdf_columns:

sample_accumulator = 0.0

if column_name not in exclude_columns:

for item in zscore_wdf[column_name]:

squared_zscore = item * item

sample_accumulator += squared_zscore

sample_covariance = sample_accumulator / float(len(zscore_wdf[column_name]) - 1)

print(f"{column_name} sample covariance: {sample_covariance}")

With the sanity check complete I proceeded to calculate the entire sample covariance matrix. There is an optimization to be had in computing only half the matrix and copying it to the other half. I did not do this because I wanted to keep things simple and focus on the math as I was developing this part of the script. To keep track of the covariance matrix I created a list that I would later turn into a dataframe, sample_covariance_matrix_list. To populate this list I created an outer loop that looped through the column names in wdf_columns using a check against the excluded_columns list because I had not yet added the wdf_columns_input variable.

This outer loop kept track of the current row while the inner loop kept track of the current column. Denoted as column_i and column_j based on the variable names I saw in covariance matrix calculations. At this point I was still yet to construct the wdf_columns_input list so I used the excluded_columns list to skip the quality and ID columns in these calculations. Inside the inner loop I constructed another loop to iterate through all the values in each column and constructed a list of products from multiplying these values together. I then summed the list of products and divided it by the length of the column minus 1 to compute the sample covariance. After sample_covariance_matrix_list was computed I converted it to a dataframe with the Pandas pd.DataFrame() method. And then converted that into a Numpy matrix for further calculation. I printed the dataframe for a data check because it looked nicer than the Numpy matrix. Python code follows.

# calculate full covariance matrix

# iterate through columns and use them to build the rows of the matrix

sample_covariance_matrix_list = []

print("\n==COVARIANCE MATRIX==")

for column_name_i in wdf_columns:

current_row = []

if column_name_i not in exclude_columns:

for column_name_j in wdf_columns:

if column_name_j not in exclude_columns:

column_i = zscore_wdf[column_name_i].tolist()

column_j = zscore_wdf[column_name_j].tolist()

counter = 0

products = []

while counter < len(column_i):

product = column_i[counter] * column_j[counter]

products.append(product)

counter += 1

product_sum = sum(products)

sample_covariance = product_sum / (float(len(column_i)) - 1)

current_row.append(sample_covariance)

sample_covariance_matrix_list.append(current_row)

#pprint(sample_covariance_matrix_list)

sample_covariance_df = pd.DataFrame(sample_covariance_matrix_list)

print(sample_covariance_df)

sample_covariance_matrix = sample_covariance_df.to_numpy()

The sample covariance matrix follows. Again the column and row names are, in order fixed acidity, volatile acidity, citric acid, residual sugar, chlorides, free sulfur dioxide, total sulfur dioxide, density, pH, sulphates, alcohol. Fixed acidity corresponds to column 0 and row 0, volatile acidity to column 1 and row 1, and so on.

==SAMPLE COVARIANCE MATRIX==

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

0 1.000000 -0.250728 0.673157 0.171831 0.107889 -0.164831 -0.110628 0.681501 -0.685163 0.174592 -0.075055

1 -0.250728 1.000000 -0.544187 -0.005751 0.056336 -0.001962 0.077748 0.016512 0.221492 -0.276079 -0.203909

2 0.673157 -0.544187 1.000000 0.175815 0.245312 -0.057589 0.036871 0.375243 -0.546339 0.331232 0.106250

3 0.171831 -0.005751 0.175815 1.000000 0.070863 0.165339 0.190790 0.380147 -0.116959 0.017475 0.058421

4 0.107889 0.056336 0.245312 0.070863 1.000000 0.015280 0.048163 0.208901 -0.277759 0.374784 -0.229917

5 -0.164831 -0.001962 -0.057589 0.165339 0.015280 1.000000 0.661093 -0.054150 0.072804 0.034445 -0.047095

6 -0.110628 0.077748 0.036871 0.190790 0.048163 0.661093 1.000000 0.050175 -0.059126 0.026894 -0.188165

7 0.681501 0.016512 0.375243 0.380147 0.208901 -0.054150 0.050175 1.000000 -0.352775 0.143139 -0.494727

8 -0.685163 0.221492 -0.546339 -0.116959 -0.277759 0.072804 -0.059126 -0.352775 1.000000 -0.185499 0.225322

9 0.174592 -0.276079 0.331232 0.017475 0.374784 0.034445 0.026894 0.143139 -0.185499 1.000000 0.094421

10 -0.075055 -0.203909 0.106250 0.058421 -0.229917 -0.047095 -0.188165 -0.494727 0.225322 0.094421 1.000000

With the sample covariance matrix computed I proceeded into calculating eigenvectors and eigenvalues. I gained a better understanding of what these are as I sorted out how to compute them. Most notably that eigenvectors are arranged as a column of values stacked on top of each other, not as a row of values one after the other. In other words eigenvectors are column vectors, not row vectors.

Second, eigenvectors are arrows pointing in a direction in a, usually, complex multi-dimensional space. In the instance of the sample covariance matrix for the wine dataset an 11 dimensional space. Eigenvalues provide a representation of variance in the data along a given eigenvector. The eigenvector with the largest eigenvalue is called the first principal component. This eigenvector quantifies the direction in the dataset with the highest variance. Skipping a head a bit for the sake of clarity the first principal component of the sample covariance matrix represented a high variance between fixed acidity/citric acid and pH. This is expected as low values on the pH scale are acidic and high values are basic. Thus as the fixed acidity/citric acid values rise the pH values are lower. As the fixed acidity/citric acid values fall the pH values are higher.

To clearly illustrate this the first eigenvector follows. I transposed the eigenvector into a row for display purposes. Note the lowest values on fixed acidity, citric acid, and density. And the highest value on pH. The density value in this eigenvector provides some insight that is not immediately obvious, at least to my basic understanding of chemistry. Wines with a lower pH tend to have a higher density, and vice versa.

fixed acidity volatile acidity citric acid residual sugar chlorides free sulfur dioxide total sulfur dioxide density pH sulphates alcohol

-0.485339 0.227143 -0.460075 -0.174506 -0.22487 0.047852 -0.015069 -0.399684 0.432844 -0.237555 0.118799

I dove into calculating eigenvectors and eigenvalues without even knowing that eigenvectors were column vectors. Everything “worked” until I had to calculate the eigenvalues which requires some matrix multiplication. The matrices have to be of the proper dimension for the eigenvalue calculation to work. At this point I had a hunch I was laying out the eigenvectors incorrectly, as rows instead of columns. As I was searching around to confirm this I discovered this seemed to be one of those things that goes without saying. At least until I found this YouTube video. It helped me gain an understanding of the layout of eigenvectors and a more intuitive understanding of the power iteration algorithm.

At this point in writing this post I stopped and watched the first ten videos in the 3blue1brown linear algebra series. I did this for my own understanding and to make sure that I had implemented the power iteration algorithm correctly. I became concerned that I had misunderstood the implementation because I found multiple sources that referenced multiplying the covariance matrix by a vector, b. What they really mean is taking the dot product of the covariance matrix and b. On to the power iteration algorithm.

The power iteration algorithm provides a method for calculating the eigenvector with the highest eigenvalue. The first step in this method is to start with a vector b that has random values. The length of the vector should be the dimension of the covariance matrix. I accomplished this with the Numpy method np.random.rand(11,1), creating a column vector with 11 random values. The next step was to take the magnitude of the vector b and divide the vector b by the magnitude to normalize it to a unit vector. The magnitude of a vector is defined as the square root of the squared sums of all the elements in the vector. I wrote my own function to accomplish this. Next I took the dot product of the sample covariance matrix and the normalized vector b. I then took the magnitude of that new vector, b1, and divided b1 by the magnitude to normalize it. I then ran this in a loop repeating the dot product and normalization steps until the values in the vector b stopped changing by a specific threshold, 0.000000000000001. I wrote a function to check for convergence between two vectors to support this loop. I multiplied the converged b vector by negative 1 before returning it to make the eigenvectors match the output from Numpy. The eigenvector can be signed either way, as long as the signs are consistent. The Python code follows.

def magnitude(vect):

summation = 0

for e in vect:

summation += e ** 2

return math.sqrt(summation)

def check_convergence(v1, v2, diff):

convergence = True

i = 0

while i < len(v1):

if abs(v1[i] - v2[i]) > diff:

convergence = False

i += 1

return convergence

def compute_eigenvalue_power_iter(covariance_matrix):

b_0 = np.random.rand(11,1)

#print("\n==b0==")

#print(b_0)

magnitude_b_0 = magnitude(b_0)

b_0_normalized = b_0 / magnitude_b_0

#print("\n==b0 NORMALIZED==")

#print(b_0_normalized)

previous_b = b_0_normalized

next_b = covariance_matrix @ b_0_normalized

next_b = next_b / magnitude(next_b)

convergence = False

while not convergence:

converged = check_convergence(next_b, previous_b, 0.000000000000001)

if converged:

break

previous_b = next_b

next_b = np.dot(covariance_matrix, next_b)

next_b = next_b / magnitude(next_b)

return next_b * -1

v_1 = compute_eigenvalue_power_iter(sample_covariance_matrix)

With that I had the first principal component as v1. The next step was to compute the eigenvalue for this eigenvector. Gemini suggested using the Rayleigh quotient to accomplish this ![]() (image from Wikipedia). Where x is v1 and x* is v1 transpose. Transposing a v1 means converting it from a column of numbers into a row of numbers. Because v1 was normalized the dot product of the transpose of v1 with v1 was 1. This simplified the calculation for the eigenvalue to only taking the dot product of the sample covariance matrix and v1, then taking the dot product of the transpose of v1 and the first dot product result. For the sake of print a nice number instead of a matrix with one number in it I extracted the result of this calculation from the result.

(image from Wikipedia). Where x is v1 and x* is v1 transpose. Transposing a v1 means converting it from a column of numbers into a row of numbers. Because v1 was normalized the dot product of the transpose of v1 with v1 was 1. This simplified the calculation for the eigenvalue to only taking the dot product of the sample covariance matrix and v1, then taking the dot product of the transpose of v1 and the first dot product result. For the sake of print a nice number instead of a matrix with one number in it I extracted the result of this calculation from the result.

first_eigenvalue = np.dot(v_1_transpose, np.dot(sample_covariance_matrix, v_1))

first_eigenvalue = first_eigenvalue[0][0]

print("==FIRST EIGENVALUE==")

print(first_eigenvalue)

The first eigenvector with the first eigenvalue. The 0 at the beginning of the eigenvector represents the Pandas dataframe index of that row. The eigenvalue indicates that that the first eigenvector represents 28.69% of the variation in the dataset.

==FIRST EIGENVECTOR==

fixed acidity volatile acidity citric acid residual sugar chlorides free sulfur dioxide total sulfur dioxide density pH sulphates alcohol

0 -0.485339 0.227143 -0.460075 -0.174506 -0.22487 0.047852 -0.015069 -0.399684 0.432844 -0.237555 0.118799

==FIRST EIGENVALUE==

3.156157933400693

I then used the Numpy linalg.eig() method to compute the eigenvectors and eigenvalues to check my work. They came out exactly the same. I was thrilled.

I then proceeded to deflate the matrix, remove the first component, and compute the second principal component. To deflate the matrix I constructed a deflation matrix by taking the dot product of v1 with the transpose of v1. Note that this is the reverse of the calculation in the bottom term of the Rayleigh quotient and results in an 11×11 matrix instead of the number 1. I then subtracted the deflation matrix from the sample covariance matrix to get the sample covariance matrix deflated by the first principal component. I repeated the power iteration algorithm with this deflated matrix to get the second principal component.

first_deflation_term = first_eigenvalue * np.dot(v_1, v_1_transpose)

sample_covariance_matrix_defalted_first = sample_covariance_matrix - first_deflation_term

v_2 = compute_eigenvalue_power_iter(sample_covariance_matrix_defalted_first)

print("\n==SECOND EIGENVECTOR==")

print(pd.DataFrame(data=v_2.T, columns=wdf_columns_input))

v_2_transpose = v_2.T

second_eigenvalue = np.dot(v_2_transpose, np.dot(sample_covariance_matrix_defalted_first, v_2))

second_eigenvalue = second_eigenvalue[0][0]

print("==SECOND EIGENVALUE==")

print(second_eigenvalue)

The second principal component shows an inverse relationship between free/total sulfur dioxide and alcohol. There is also a smaller inverse relationship shown between (volatile acidity, residual sugar, density) and alcohol. The eigenvalue indicates this eigenvector accounts for approximately 17.05% of the variation in the dataset. The second eigenvector and eigenvalue follow.

==SECOND EIGENVECTOR==

fixed acidity volatile acidity citric acid residual sugar chlorides free sulfur dioxide total sulfur dioxide density pH sulphates alcohol

0 0.102328 -0.288786 0.146508 -0.252262 -0.153133 -0.517022 -0.577393 -0.217537 0.006374 0.06228 0.381635

==SECOND EIGENVALUE==

1.8782613986038976

At this point I had all the values I needed to create a 2 dimensional plot to show any relationships between the first and second principal components. I went ahead and calculated the third principal component using the same deflation method so that I could also construct a 3 dimensional plot of the first three principal components.

second_deflation_term = second_eigenvalue * np.dot(v_2, v_2_transpose)

sample_covariance_matrix_defalted_second = sample_covariance_matrix_defalted_first - second_deflation_term

v_3 = compute_eigenvalue_power_iter(sample_covariance_matrix_defalted_second)

v_3_transpose = v_3.T

third_eigenvalue = np.dot(v_3_transpose, np.dot(sample_covariance_matrix_defalted_second, v_3))

third_eigenvalue = third_eigenvalue[0][0]

print("\n==THIRD EIGENVECTOR==")

print(pd.DataFrame(data=v_3.T, columns=wdf_columns_input))

print("==THIRD EIGENVALUE==")

print(third_eigenvalue)

The third principal component. This eigenvector and eigenvalue pair show a high positive loading on volatile acidity. And a high negative loading on alcohol, free sulfur dioxide, and total sulfur dioxide. This indicates an inverse relationship between these features.

==THIRD EIGENVECTOR==

fixed acidity volatile acidity citric acid residual sugar chlorides free sulfur dioxide total sulfur dioxide density pH sulphates alcohol

0 0.122376 0.443718 -0.246843 -0.091359 0.052562 -0.428288 -0.323424 0.334238 -0.059923 -0.302768 -0.470201

==THIRD EIGENVALUE==

1.573652089799959

With the three principal components computed the next step was to use them to project the data from 11 dimensions down to 2 and 3 dimensions. This involved creating a projection matrix consisting of the first principal component as column 1 and the second principal component as column 2. I used the Numpy hstack() method to accomplish this. I then took the dot product of the wine dataset inputs and the projection matrix to project the data from 11 dimension down to 2 dimensions. The principal components served as the axes on the 2D graph.

projection_matrix = np.hstack((v_1, v_2))

print("\n==PROJECTION MATRIX==")

print(projection_matrix)

projected_data_matrix = zscore_wdf_inputs_matrix @ projection_matrix

print("\n==PROJECTED DATA MATRIX==")

print(projected_data_matrix)

x_data = projected_data_matrix.T[0]

y_data = projected_data_matrix.T[1]

colors_data = zscore_wdf['quality'].to_numpy().T

plt.scatter(x_data, y_data, c=colors_data, cmap='GnBu', s=3)

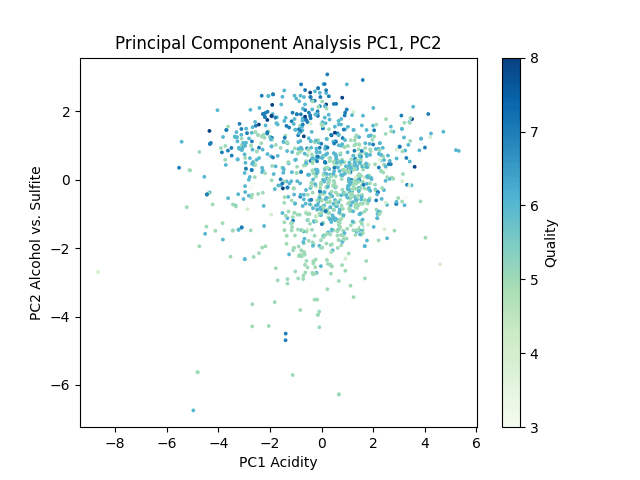

plt.xlabel("PC1 Acidity")

plt.ylabel("PC2 Alcohol vs. Sulfite")

plt.title("Principal Component Analysis PC1, PC2")

plt.colorbar(label='Quality')

plt.show()

This resulted in the following graph.

Each dot on this graph represents a wine in the dataset, color coded by quality. This graph shows that the first principal component, while accounting for 28.69% of variation in the dataset, seemingly has little relation to the clustering of wine quality. The second principal component indicates some quality clustering around high alcohol content.

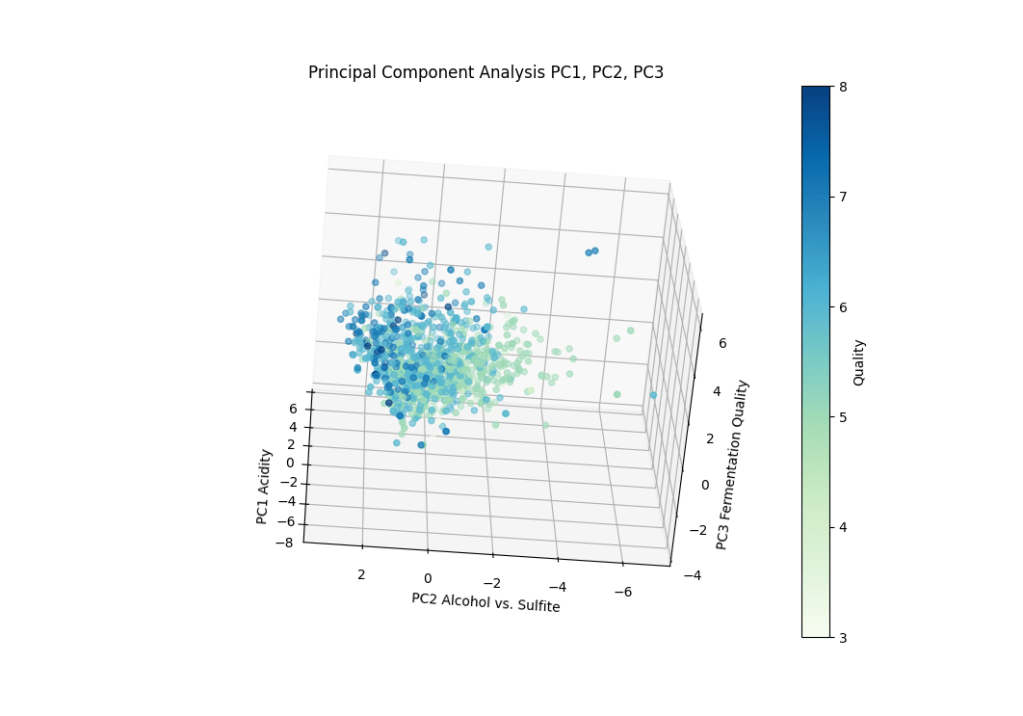

I repeated the process of creating a projection matrix with the first three principal components to obtain a 3 dimensional scatter plot.

projection_matrix_3d = np.hstack((v_1, v_2, v_3))

print("\n==PROJECTION MATRIX==")

print(projection_matrix_3d)

projected_data_matrix_3d = zscore_wdf_inputs_matrix @ projection_matrix_3d

print("\n==PROJECTED DATA MATRIX==")

print(projected_data_matrix_3d)

x_data_3d = projected_data_matrix_3d.T[0]

y_data_3d = projected_data_matrix_3d.T[1]

z_data_3d = projected_data_matrix_3d.T[2]

fig, ax = plt.subplots(subplot_kw={"projection": "3d"})

p_3d = ax.scatter(x_data_3d, y_data_3d, z_data_3d, c=colors_data, cmap='GnBu')

ax.set_xlabel('PC1 Acidity')

ax.set_ylabel('PC2 Alcohol vs. Sulfite')

ax.set_zlabel('PC3 Fermentation Quality')

ax.set_title('Principal Component Analysis PC1, PC2, PC3')

fig.colorbar(p_3d, ax=ax, label='Quality')

plt.show()

Rotating the plot around shows a slight clustering of quality around the PC3 axis with more positive values. This would indicate higher alcohol content and tracks with the clustering demonstrated by PC1. This clustering seemed much less pronounced than the clustering observed in PC1.

At this I considered the Principal Component Analysis portion of the module complete. I asked Gemini if there was anything else I should know and practice before moving on and it came up with a number of suggestions. Creating a Scree Plot, deciding how many principal components to keep based on Cumulative Variance, and non-linear methods to analyze the data. I will detail these in future posts.

Leave a comment